A post written in Buenos Aires for ‘Death Cafe‘ which is more about life than death – it concerns the ‘final furlong’.

For some – you might say ‘the lucky ones’ – death comes in old age, suddenly, painlessly and without warning. Others may face a long and challenging ‘final furlong’. Those of us in this group will need to prepare for death if we are to get it right – or as right as preparing for an unknown death can ever be.

Preparing for change is often one of our most difficult tasks as we age. We may be distracted by other concerns, in denial about our mortality, or simply too frail to address it. The one inevitability is that we will not escape it; so there is need to prepare well for a ‘good death’.

I shall be dealing with several aspects of ‘the final furlong’. My list is not exhaustive, nor my opinion definitive. There is more to be said, and I hope readers will add their experience and insight to produce the best-crafted approach to the process of infirmity, dying and death. Of particular interest is the less visible group who face the final furlong prematurely, before age can justify demise.

THE NUTS AND BOLTS

As it is unlikely that you will be given sufficient, if any advance warning of death, this advice is applicable to every adult, irrespective of age.

The first essential – to make a Will.

Recently, as a barrister I was instructed by the Official Solicitor to deal with an application in the Court of Protection on behalf of a dying woman. When younger, she had made a Will, but in the meantime her son – her sole beneficiary under her Will, had died. She was however fortunate in her final years to be cared for by a devoted step-daughter who lived with her. These were happy years until the old lady developed dementia. It was then that her historic (and now useless) Will was discovered, and her incapacity made it too late for her to make a new one.

Under the rules of Intestacy her step-daughter would receive not a penny. Within the list of the distant relatives to benefit, none had maintained contact with the old lady and most knew not of her existence. Using its inherent powers, the court indicated that it would change the Will in favour of the step-daughter, adding that there had rarely been a more deserving case. Yet the night before the hearing, the old lady died, and her step-daughter was forced to leave her home with just her clothes after 15 years as unpaid resident carer.

This tale tells of a bigger story. It speaks of the need to make, and review your Will to take account of your present circumstances. The ‘old Will in a drawer’ may be your last iniquity to a well-spent life.

My advice: after the age 25 make a Will, and update it as your life circumstances change. In later life, address your choices ‘root-and-branch’ to ensure your Will is appropriate and fair. Make a list of everything you possess, from real estate (houses and land), shares, policies and pensions – to other assets such as savings, vehicles, jewellery; then list their location. Set out your wishes in simple terms. A solicitor may prepare this for a charge, but it is possible to make your own Will by following this simple free guidance here.

The second essential – to prepare two powers of attorney.

As we age we lose capacity. At first this may be simply ‘a senior moment’ and a forgotten name. Few people reach the end of life with both memory and reasoning intact. In the future there will be many more elderly people with cognitive deficit. More concerning for a younger generation is the possibility of loss of capacity through trauma, such as car accident, major illness or stroke.

Most incidents of loss of capacity come suddenly and without warning. So it is wise to prepare powers of attorney that enable a relative or friend to make important decisions on your behalf should you lack capacity. There are two powers of attorney – one for health and welfare decisions; one to manage financial affairs. They cannot be exercised against your will, so that should not be a reason for failing to take this step.

My advice: make both at any age beyond 40 years. There is a cost to register your powers of attorney, but the cost is infinitesimal compared with the professional charges that will be involved should this choice be neglected. Ask a family member to assist you, or prepare both using the government’s on-line free service here.

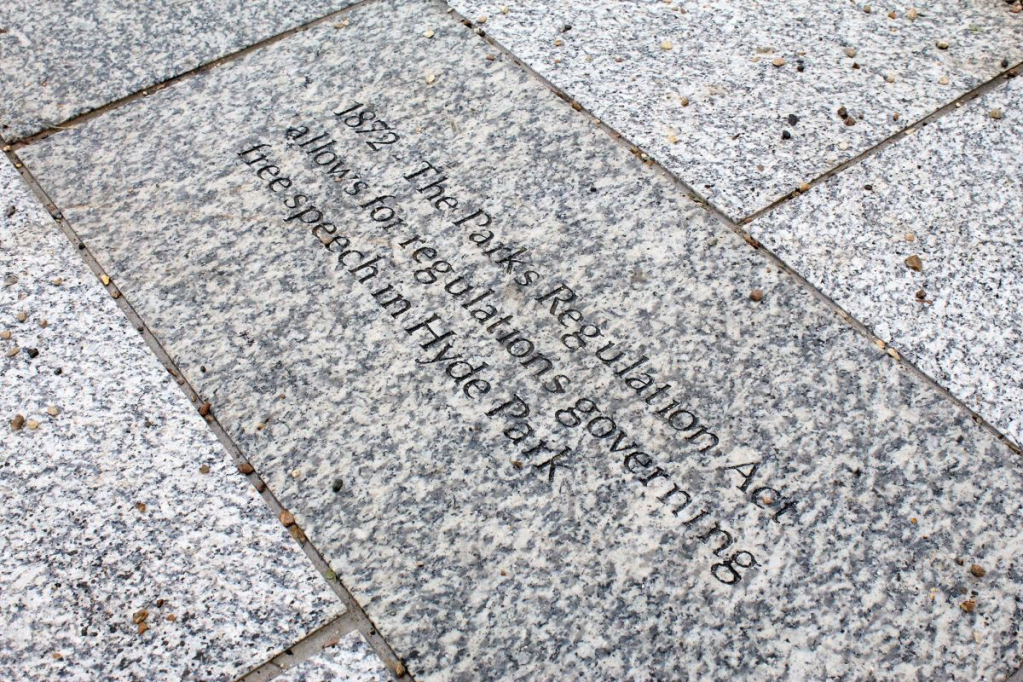

The third essential – to make an Advance Decision and Advance Statement.

The advance decision sets out your instructions concerning your medical care at the end of life. Properly made and recorded, it is binding on medical professionals and relieves distressed relatives of difficult, sometimes divisive decisions. Whilst assisted dying is not currently a legal option in the UK, supported dying is. So this is your chance to specify the extent of care you would seek at various stages when your death is imminent, or should worthwhile existence have ceased.

You will be relieved to know that your advance statement is a more creative document. Here you state your preferences for care should you not be able to articulate them when the time comes. These may include where you would prefer to end your days, how and by whom you wish to be cared, by what name you wish to be addressed, what food, music and interests are important to you, and as important, what you would wish to avoid.

Preparing both the decision and the statement are simple using the free Compassion in Dying on-line support here.

Those facing terminal care should also make an advance care plan. For this you need to consult your treating physician when the time comes. Ensure that your advance decision and advance statement are attached to the care plan.

BEYOND THE BASICS

Prepare your own funeral / other arrangements.

Whilst to some this sounds a morbid topic (which it is), others find it quite empowering. You will not experience what you plan, but by preparing in advance, your family will be spared much work, stress, distress, and probably many arguments as to what is best.

At the most basic level, would you wish to be buried or cremated? Where would you wish to be buried or have your ashes scattered, how and by whom?

My mother chose her own funeral director – someone who she had known and respected. She pre-paid her funeral arrangements, as a sculptor, carved her own memorial stone, and specified the exact position where her ashes should be placed. On her death all that was required was a simple phone call – everything else was sorted.

My advice: prepare a plan. Humorously mark it “It’s My Funeral’, leave a list of who you wish to be invited, and how they may be contacted. Why not choose your favourite music, hymns, readings, and set out your wishes for a funeral breakfast or wake? Make provision for this within your Will so that the cost is clearly covered and not contested.

Where do you want to die?

In ‘The lady and the Reaper’ film we witness the conflict between the medical profession and the Grim Reaper. Hopefully, your advance decision will have taken care of this particular battle.

But there remains the issue of where you would wish to end your days. I have visited splendid care homes that are well staffed with caring people – yet often I sense the tediousness of day-to-day existence that many residents experience in a care or nursing home.

Towards the end of my mother’s life, remaining in her own home with support afforded her access to all that was familiar in a location where friends could drop by.

Others may not be so fortunate. Removal to a care home can be confusing and may be distressing. For those with mental capacity, the move is itself a form of bereavement when they let go of possessions and familiarity.

My advice: Write down your wishes. If you own your home, assess its suitability for old age, advancing infirmity and ‘the final furlong’. What is needed to allow you to remain there? Can it be adapted to afford you ground floor living? What about electronic, key-less entry for family, visitors and carers? What is the value of your home should you need to move? What other accommodation will your equity and savings afford? If you do not own your home, what alternatives are out there by way of retirement or sheltered accommodation?

If you reach the stage where you may need hospital care, do you really want to undertake this last journey and face death in a hospital bed? If not, your family and friends need to know your wishes and feelings, so that they can be respected.

Departing with dignity and saying goodbye

Most of us reach the end of life with unfinished business. It may be an argument with a relative or friend, or an unspoken acknowledgment of love, thanks or support. At the simplest level it could just be who you would wish to be informed when you die.

My advice: make a list of who you wish to be told of your death, and how they can be contacted. Write letters to those that you love, respect and will miss, together with those that you know will feel your loss. Should you have outstanding issues, you can address them in a letter sensitively – understanding that there can be no reply.

In Mitch Albom’s ‘Tuesdays with Morrie’, facing end of life, Morrie was asked what he valued most in life. His answer was unsurprising – ‘family, friends and relationships’.

Perhaps, by way of acknowledgement or repair, a word of thanks or forgiveness to our family, friends and those we have known and valued can be our final parting gift before we die?

Stephen Twist © 2017 for Death Cafe

With thanks to YG2D.com for the photo

Whilst an advert may appear at the foot, this blog is neither monetarised, nor endorsing any product

Your computer/laptop’s internal microphone is not adequate. It will produce fuzzy and buzzy feedback. I have

Your computer/laptop’s internal microphone is not adequate. It will produce fuzzy and buzzy feedback. I have