A post examining vehicle recognition and control in the digital age

Others will write about Barcelona and Cambrils – recalling Paris and London. They may address urban terrorism that has reached Turku, and even comment on Herat mosque, Lahore, Lake Chad, Abyan, Kirkuk, Bajaur, Quetta, Burkina Faso, Kunduz, and Konduga. August 2017 saw 113 global terrorist events, involving 494 innocent deaths.

Academic analysis would reveal the number of terrorist incidents involving motor vehicles used for travel to – and escape from, as well as perpetrate terrorism. Today’s radio conversation is about ‘hiring vans to terrorists’. And tomorrow?

Road traffic deaths in the UK for the year ending March 2016 were 1,780, with 24,610 people killed or seriously injured, and 187,050 casualties of all severity. Cyclist’s deaths comprise 100 in the same year, whilst serious injuries amount to 3,239 and lesser injuries 15,505. Motor traffic levels rose in that year by 1.8%.

I think you see where I am going. Now don’t get me wrong: I like vehicles. I have owned and driven many kinds over four decades, from large motorcycles to HGVs, and still own three – a motor home, car and roadster. But, like me, do you see the writing on the wall – that says ‘top gear motor days are over’?

With the advent of driverless, electric-powered cars, we entered a digital motoring age. Top of the range vehicles – including BMW and Mercedes with conventional engines – inform you remotely where they are, how they are, what they need, what they are doing, having the capacity to park themselves. They ‘live and breathe information’, with which our smart phones light up at any distance.

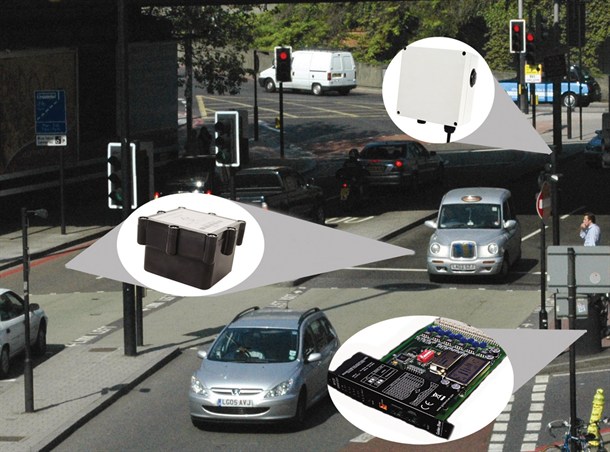

It seems that the days of the incognito car are numbered. We have electronic number plate recognition, so it is a small step to the digitally identified vehicle; one that can be tracked remotely, and importantly, controlled remotely.

When travelling on UK roads and motorways, I am constantly amazed by the speed of some passing cars. More alarming is their closing and stopping speed. The combination of driver error and irresponsibility is fatal. Now what if those vehicles could be remotely managed?

It has always seemed to me to be an absurdity that vehicles for UK roads are still sold on the basis of speed. Assuming use on public roads with a 70 mph limit, how is this appropriate? Why do we tacitly promote the acquisition of high performance cars? On 13 March 1996, seventeen innocent deaths in Dunblane resulted in the abolition of handguns. So why in 2017 do we tolerate a massive car-death toll?

How would it be if all UK road vehicles (with the exception of emergency services) were fitted with speed regulators linked to GPS and road-side sensors that controlled maximum speed depending on road classification, and even road conditions? Why simply detect and fine, when you can regulate?

How many lives might be saved? How many vehicles involved in crime may be traced? And, when actively used for criminal or terrorist prevention purposes, how many vehicles could be identified, targeted and electronically slowed and brought to a stop – upon leaving a carriageway, or by police in pursuit?

Of course the ‘motoring rights lobby’ will screech in anguish, neglecting the fact that irresponsible exercise of their rights frequently deprives innocents of lives and families of loved ones. We would have to ‘get over’ the fact that, unlike people, vehicles fall into the category of accountable property, and that our movements with and within them would be traceable.

What is the current price of vehicular freedom? Is it worth it? If ‘freedom’ is really what you want, why not buy a bike and take the risk with the rest of us?

Whilst an advert may appear at the foot, this blog is neither monetarised, nor endorsing any product