A post about freedom of speech – protection, balance and proportionality

This week, with outpourings of grief following the death of Queen Elizabeth II, a minority of anti-Monarchists have had to bite their tongues, adjudging that now is not an appropriate moment to vent their political and social views. However some from the fanatical fringe, or the impetuous immature, have shown out with protests and insults that have offended a distressed nation. They have been arrested and removed. They have been silenced.

The eighteen articles in Schedule 1 Part 1 of the Human Rights Act 1989 provide a barrage of rights protected by law. In particular Article 10 provides for freedom of expression. The protection is not, however, unqualified.

‘The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.’

As a lawyer I cannot but imagine that the actions of police have been lawful in the present circumstances. The response from the Monarchists alone – including the swinging of fists – justified police action to prevent a breach of the peace. On the other hand libertarian commentators such as Brendan O’Neill writing in the Spectator have challenged the concept of silencing this minority, contending that their freedom of speech is ‘the most essential liberty’.

Of course that is to mount the right of a protester way above the interests of the general public that may not share their views. Whilst some of us might agree with O’Neill conceptually, where we depart is in the manner of exercise of protest. We have issues with the shouting of an obscenity, just as we do with the blocking of a motorway by protesters.

The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 has gone some way to amend the Public Order Act 1986, but both Acts failed to achieve a social balance between the protection of free speech and the prevention of harm.

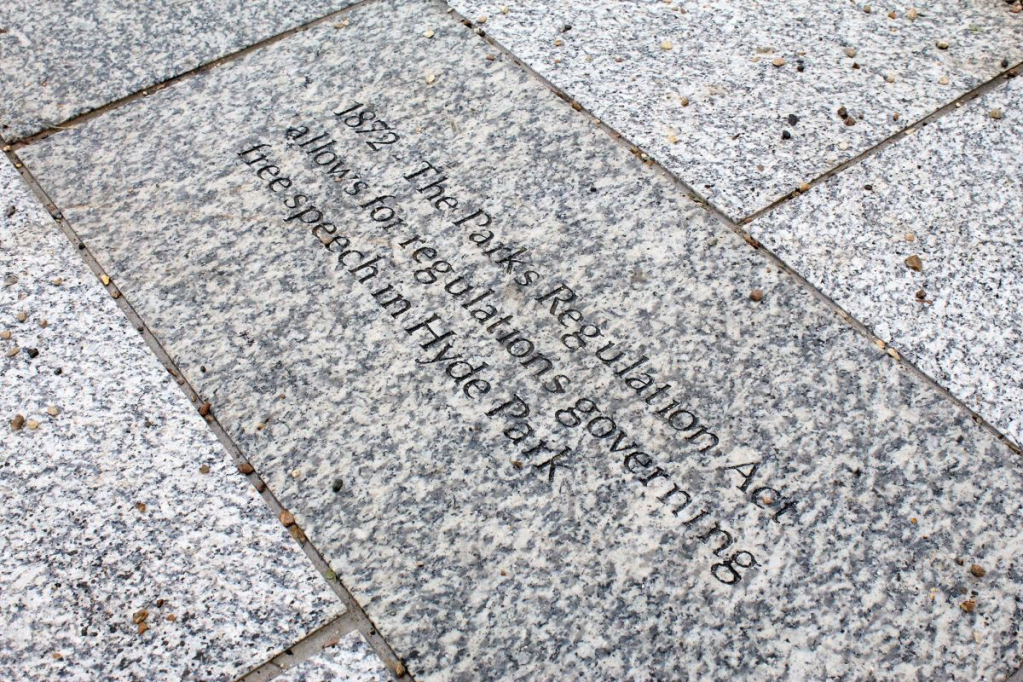

That got me looking back to 1872 and the Parks Regulation Act which enshrined the right to protest at ‘Speakers’ Corner’, Hyde Park London. It built on the long-held right of those to be executed at Tyburn Gallows to make a final speech there before their hanging. In 1866 the Reform League, being locked out of the park, removed the railings so as to gain entry and by the next year Home Secretary Spencer Walpole resigned when police and troops declined to intervene against the protesters.

Perhaps Prime Minister Truss should consider new ways to protect the freedoms of thought and expression, whilst responding to the public desire for proportionality of protest. Designating safe protected protest venues, as was done at Hyde Park, might go some way to achieve this, as would the recognition of prescribed methods of protest that balance free speech with public order?

Advertisements appearing below this post are placed by the platform not the writer. They are neither endorsed nor monetarised.